On March 5, 1974, 17-year-old Amy Billig left her home in Coconut Grove, Florida, planning to hitchhike to her father’s art gallery. She never made it there.

Early Life of Amy Billig

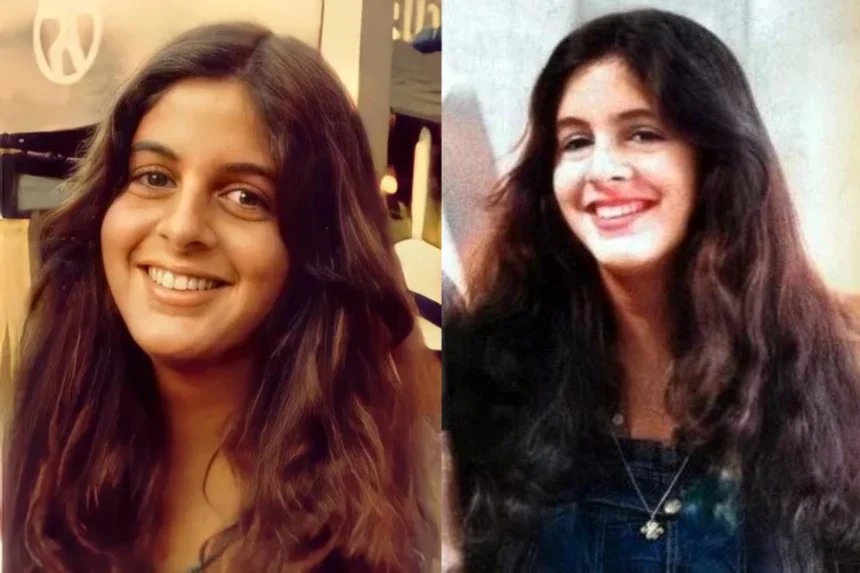

Amy Billig was born on January 9, 1957, in Oyster Bay, New York, to Nathaniel Solomon Billig and Susan Billig. Her father ran an art gallery, while her mother was an interior designer and art dealer. The Billigs were a Jewish family with two children — Amy and her younger brother, Joshua.

Friends described Amy as friendly, curious and deeply spiritual. Her mother said she was “very much into nature.” She played the flute and guitar, wrote poetry, read constantly and even trained dolphins at the Miami Seaquarium.

In 1969, the Billigs moved from New York to Coconut Grove, Florida, hoping for a safer environment. Amy fit right in with the Grove’s creative atmosphere. By her senior year of high school, she was thinking about acting after graduation. She stood 5’5″, weighed 110 pounds, had long brown hair and a small scar from an appendectomy.

Amy didn’t have a car, so she sometimes hitchhiked — a habit that was fairly common among teens in the 1970s, even though her parents worried.

The Day Amy Vanished

The day she disappeared started like any other. Amy came home from school, had a yogurt and called her dad to ask for two dollars for lunch with friends. After changing her blouse, she grabbed her bag and walked out the door. She was last seen hitchhiking near Poinciana Street and Main Highway — only a few blocks from her home.

She wore a denim miniskirt and cork platform sandals. Construction workers saw her by the road but no one saw what car she got into. She never made it to her father’s gallery or met her friends.

When Amy didn’t come home that night, her friends called, worried. Her mother immediately contacted police but an official search didn’t begin until the next morning after Susan made another desperate report at 6 a.m., per Wikipedia.

Miami police quickly opened an investigation. Detectives interviewed Amy’s friends, retraced her last known route and searched the places she often went. Because she hadn’t taken personal belongings, police believed she hadn’t planned to run away. The leading theory became that Amy had been abducted while hitchhiking.

Two weeks later, on March 18, a hitchhiking college student found Amy’s Instamatic camera about 250 miles north of Miami near Florida’s Turnpike.

Most of the film was overexposed but two pictures stood out — one of a light-colored pickup truck parked near a vine-covered building and another of a white van. Investigators couldn’t trace either vehicle or the location. Those photos were the only physical evidence ever found.

The Fight to Find Amy

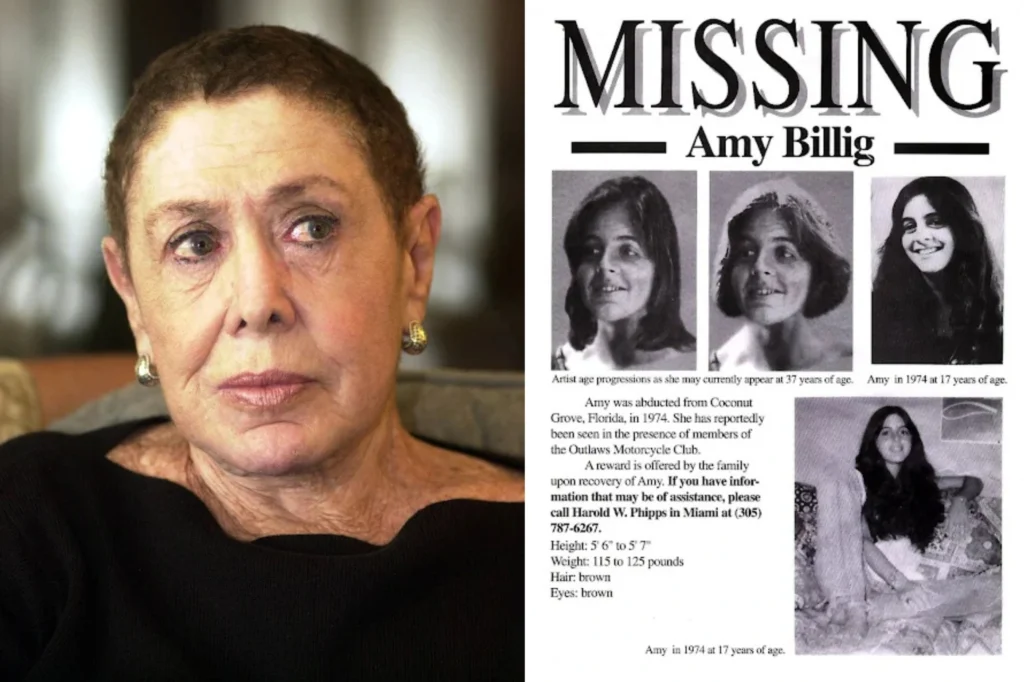

The Billig family refused to wait around. Susan and Nathaniel hired a private investigator, handed out hundreds of missing-person flyers and called every lead they could find.

Local media picked up the story and the family offered a $1,000 reward that later grew to several thousand dollars thanks to donations — including $1,500 raised at a local high-school music festival.

Then came the first serious leads. Police learned that two motorcycle gangs — the Outlaws and the Pagans — had been traveling through Coconut Grove the same day Amy vanished. Both groups were known for violence, drugs and frequenting the area during bike week.

A woman calling herself “Susan Johnson” told investigators that Amy had been taken by the Outlaws. Days later, two gang members actually showed up at the Billig home. They told the family they’d find Amy if she was with them — but later called again, telling them to “forget the whole thing.”

Another possible sighting came from a convenience-store manager in Orlando who said he saw a girl matching Amy’s description with two bikers buying vegetarian soup. That detail mattered — Amy was vegetarian but that fact hadn’t been made public.

Ransom Demands and Cruel Hoaxes

Sixteen days after Amy’s disappearance, the Billigs got a ransom call demanding $30,000. Susan borrowed the money from friends and arranged a meeting at Miami’s Fontainebleau Hotel. But she refused to hand over the cash without proof that Amy was alive.

Police soon arrested the callers — 16-year-old twins Charles and Lawrence Glasser. They were scammers, not kidnappers. Both pleaded guilty and were sentenced, the Journal News reports.

Heartbroken and furious, Susan said publicly, “Please no more crank calls like that one. I would have done anything to get [Amy] back—begged, borrowed or stolen.”

But the cruelest torment was still to come.

Soon after the hoax, Susan began receiving disturbing phone calls. The man on the line claimed Amy was alive, described graphic abuse and taunted her for hours. The calls went on for years — sometimes daily, sometimes with long breaks in between — and always from pay phones, making him impossible to trace.

For 21 years, Susan endured the harassment, hoping each call might reveal a clue. In October 1995, the FBI finally caught the caller. He was Henry Johnson Blair, a married father who worked for U.S. Customs. Blair was arrested and convicted of stalking.

Susan, exhausted but still searching for answers, said, “I just don’t understand why he pinpointed me and Amy. There has to be a reason.” She later filed a $5 million lawsuit against him which was settled out of court.

The Nationwide Hunt

Despite everything, Susan didn’t stop searching. She followed leads across the country — to Oklahoma, Nevada, Washington and even the United Kingdom.

One man in Oklahoma named David claimed to have “owned” Amy and even described a private scar she had. That lead collapsed when violence broke out among his associates before police could intervene.

Another time, a body found in Texas was thought to be Amy’s but dental records ruled it out.

Even psychics joined the case. In the 1980s, one claimed Amy had died after being assaulted and her remains scattered underwater. Nothing came of it but the case stayed alive in the public eye.

By the 1990s, Susan’s relentless search became nationally known and Amy’s story appeared in several documentaries and talk shows.

A Deathbed Confession

More than two decades after Amy vanished, a breakthrough came — or at least, what seemed like one.

In December 1997, Paul Branch, a former high-ranking member of the Pagans motorcycle gang, made a deathbed confession. He admitted that the gang had abducted Amy, taken her to a party in the Everglades and assaulted her.

According to his statement, Amy fought back, angering the men. They injected her with drugs to silence her and she overdosed. Her body, he said, was dumped in a swamp, according to Tampa Bay Times.

Branch had been questioned many times before but had never said this. Detective Jack Calvar, who led the case, confirmed that the confession matched details only police knew. Still, no physical evidence was ever found. Calvar later said, “We will never find a body.”

Even after that confession, Susan refused to completely give up hope. For more than thirty years, she carried photos of Amy everywhere she went. Her husband, Nathaniel, died in 1993 from lung cancer. Susan passed away in 2005 after her own battle with the disease.

In one of her last interviews, she said, “When your child is never found … there is no line you cross that tells you to quit hoping and looking. To give up would be a terrible betrayal.”

Remembering Amy

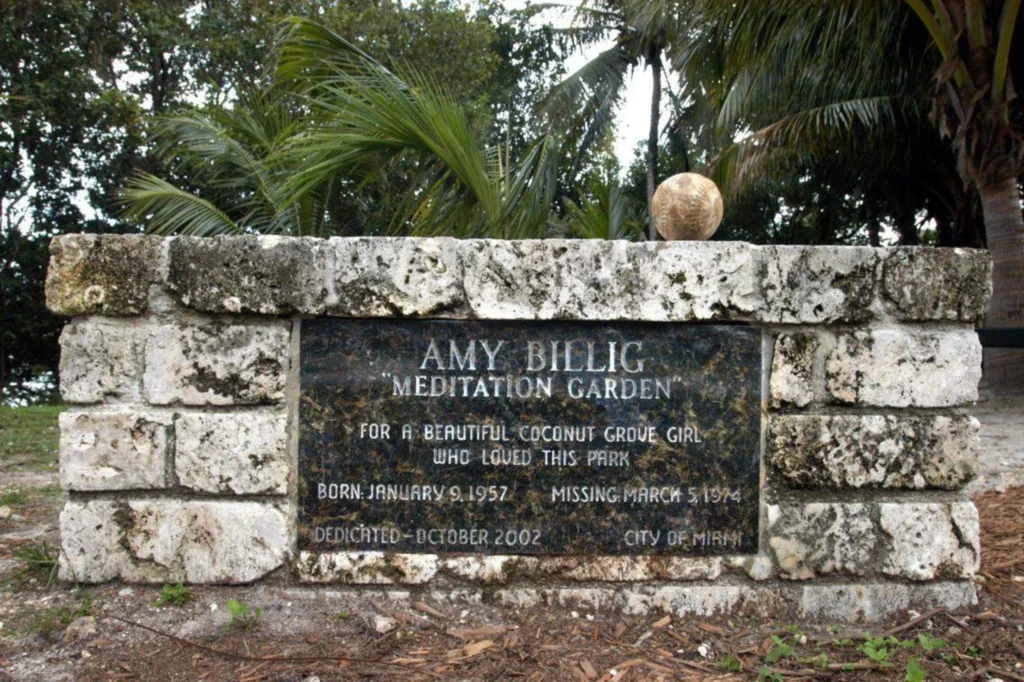

In 2002, the Amy Billig Meditation Garden was created in Coconut Grove as a peaceful memorial. A stone marker designed by Amy’s brother Joshua stands there, surrounded by flowers. The garden became a quiet place for reflection — a tribute to Amy’s life and her mother’s determination.

Amy’s story continues to appear in documentaries and true-crime shows, keeping her memory alive. Her case was featured in:

- “Stalking: A Mother’s Nightmare” (1997), a documentary about Susan Billig’s experience with the harassing caller.

- “Searching for Amy” (BBC, 1998), which followed Susan’s investigation.

- A&E’s “Investigative Reports” in 1998.

- Two episodes of “Unsolved Mysteries” covering the disappearance.

Susan also wrote a book, “Without A Trace: The Disappearance of Amy Billig – A Mother’s Search for Justice,” published in 2001, where she shared her decades-long search for truth.

Fifty years later, Amy Billig’s disappearance remains one of Florida’s most haunting cold cases. Despite confessions, theories and decades of leads, no trace of her has ever been found.

Let’s dig into the legal side of hoax calls and harassment.

Criminal Liability for Hoax Calls and Harassment in Missing-Person Cases

Hoax calls and harassment in missing-person cases waste time and mess people up. Families who are already terrified get targeted by scammers and random creeps who use their pain for fun or attention. It’s not just cruel, it’s scarring. Stuff like that sticks with people for years, long after the case is old news.

In the U.S., making fake ransom calls or messing with families of missing people isn’t some twisted joke. It’s a serious crime. Depending on what someone does, it can count as extortion, false reporting, stalking or even obstruction of justice.

And while the pranksters think it’s just a game, there’s always a real family on the other side, heartbroken and still hoping for answers.

Understanding Hoax Calls

A hoax call in a missing-person case usually starts with fear. Someone pretending to have information — or worse, pretending to have the missing person — reaches out with an urgent story. There’s almost always a demand for money, a tight deadline and no proof that the victim is alive.

The FBI calls these extortion schemes “telephonic coercion.” A fancy term for using phone calls to force families into paying money under threat or emotional manipulation. According to the Bureau, these criminals take advantage of the raw panic that sets in during the first few days after someone disappears.

The scam often begins with social media. Families share photos, descriptions and contact info while pleading for help and scammers are watching. They collect every detail they can find: the missing person’s nickname, the clothes they were wearing, even the mother’s phone number from a Facebook post.

Within hours, someone calls saying, “We have your daughter. Send $7,000 or you’ll never see her again.”

That’s not a random number, by the way. According to recent FBI data, most fake ransom demands fall between $5,000 and $10,000 — usually around $7,000 — just enough to seem believable but not impossible.

And these scammers are getting smarter. They use burner phones, encrypted messaging apps and caller ID spoofing to hide who they are. Some even fake background noises — traffic, crying, muffled voices — to sound more convincing. Families hear what they want to believe and panic takes over logic.

The emotional toll is devastating. Parents stay up all night waiting for another call, terrified of missing a chance to bring their child home. And every minute spent chasing a hoax is a minute lost from the real search.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of these scams reportedly increased. With more people isolated online, sharing updates publicly, fraudsters found new openings. Social media became both a lifeline and a trap.

Harassment Linked to Missing-Person Investigations

Hoaxes are one kind of cruelty. Harassment is another.

When a person goes missing, families often get bombarded by anonymous calls, messages and even fake “tips.” Some of them come from trolls who enjoy the chaos. Others are from disturbed individuals who gain some twisted satisfaction from causing fear.

Harassment can look like constant phone calls at night, graphic messages or claims like “I know where your daughter is.” Some callers pretend to be witnesses. Others impersonate police officers.

In legal terms, that’s stalking and harassment but to the families, it feels like torture. It keeps them trapped in a state of confusion, unable to tell what’s real. It is an emotional warfare disguised as communication.

The FBI and local police see these cases as serious crimes because they drain investigative resources. Every fake lead has to be checked. Every phone call has to be traced. That means fewer people working on genuine evidence.

Under most state and federal laws, repeated harassment, especially when it causes emotional distress can lead to criminal charges. Depending on how bad it gets, the penalties can include hefty fines, restraining orders or years in prison.

Legal Consequences for Hoax Calls and Harassment

If someone calls a family pretending to have their missing loved one, that’s not just a bad prank. It’s extortion — a felony in every U.S. state. The law looks at intent: if the person deliberately tried to get money through fear, it counts as a crime even if no money was ever exchanged.

Then there’s false reporting which covers lying to police, if someone pretends they saw a missing person or gives fake info about where they are, it counts as obstruction of justice. Both can lead to serious legal trouble and even prison time.

When it comes to harassment and stalking, the punishment can change depending on what happened but it’s never something small. The federal anti-stalking law in the U.S. (18 U.S.C. § 2261A) covers both regular stalking and cyberstalking — such as using texts, calls or emails to scare or harass someone.

There isn’t one set sentence but the law points to other sections that decide how bad the penalty is. If someone causes serious harm or uses a weapon, they could be looking at years in prison.

Courts take into account the lasting trauma these acts cause. In many cases, families of missing persons end up needing therapy or relocating because of ongoing harassment. Judges often describe such crimes as “an attack on the grieving process itself.”

Investigative and Law Enforcement Response

Once a hoax or harassment complaint is reported, law enforcement usually treats it as a high-priority investigation. The FBI and local police departments coordinate to trace phone numbers, subpoena records and track digital footprints.

The FBI regularly urges families to document everything — from text messages and call logs to screenshots and emails. These details help build cases later. In many cases, agents can use call-tracing technology or IP address tracking to find out where the communication originated.

The Bureau also runs public awareness campaigns warning about fake ransom scams. They tell families never to send money without clear proof of life and to let police handle communications with suspected kidnappers.

Police often partner with tech companies and telecom providers to expose offenders hiding behind VPNs and spoofed numbers. The process can be slow but successful cases usually lead to federal charges, especially when interstate communication is involved.

Technology and Social Media’s Role

Social media changed how missing-person cases unfold and not always for the better.

Families use Facebook, X (formerly Twitter) and TikTok to spread the word but criminals see opportunity. They mine those posts for names, dates, phone numbers and personal clues. The more emotional the post, the easier it is to exploit.

A scammer might say, “I found your daughter’s phone near a gas station — send $500 so I can ship it back.” The message looks harmless but it’s designed to hook families into conversation. Once contact is made, the demands grow.

Tech has also made hiding easier. With caller ID spoofing, VPNs and anonymous messaging apps, offenders can operate from anywhere — another country, another continent and still sound local. That’s why investigators are working closely with cybersecurity teams to detect digital fingerprints left behind in these cases.

Experts say the best defense is digital awareness, limiting what’s shared online, setting privacy filters and keeping contact numbers private can reduce exposure. The FBI and the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) both encourage families to report suspicious messages or calls immediately.

Preventative Measures and Victim Guidance

Families in the middle of a missing-person crisis are vulnerable — emotionally, financially and mentally. Scammers know this. That’s why authorities urge them to take a few key steps:

- Limit personal info online

- Document everything

- Report quickly

- Never negotiate

- Seek emotional support

The FBI’s guidance is clear: “Do not engage with suspected hoax callers. Report all incidents swiftly.” This isn’t just for evidence collection — it’s for safety.

Why Accountability Matters

Every time someone pulls a hoax call or sends a threatening message, they’re breaking the law and taking away the little bit of hope those families are holding onto. They waste the energy of investigators who could be working to find real answers. They turn tragedy into personal entertainment or profit.

The U.S. legal system recognizes this as more than simple mischief. It’s emotional exploitation, that’s why prosecutors push for harsh penalties — not only to punish but to deter others.

The goal is simple. It is to protect families from being victimized again while they are already suffering.

Final Thoughts

Hoax calls and harassment in missing-person cases sit at a disturbing crossroads between cruelty and crime. The law may classify them as extortion or stalking but in reality, they’re acts of psychological violence.

Legal frameworks in the U.S. are growing stronger and investigators are getting better at tracking digital crimes. But awareness is still the first line of defense. Families, advocates and even online communities play a vital role in spotting and reporting exploitation early.

As the FBI keeps reminding the public — “If it feels wrong, it probably is.”

And when it comes to missing-person cases, one false call can mean losing more than just time.