On a Sunday morning, September 5, 1982, 12-year-old paperboy Johnny Gosch left his home in West Des Moines, Iowa, before sunrise. It was supposed to be an ordinary day. Another early morning delivering newspapers. But Johnny never came home. His disappearance stunned the country and eventually changed how America responded to missing children.

Early Life of Johnny Gosch

John David Gosch was born on November 12, 1969. He grew up in a typical suburban neighborhood, surrounded by family and friends who adored him. People who knew Johnny described him as polite, responsible and hardworking. A boy who took pride in his paper route.

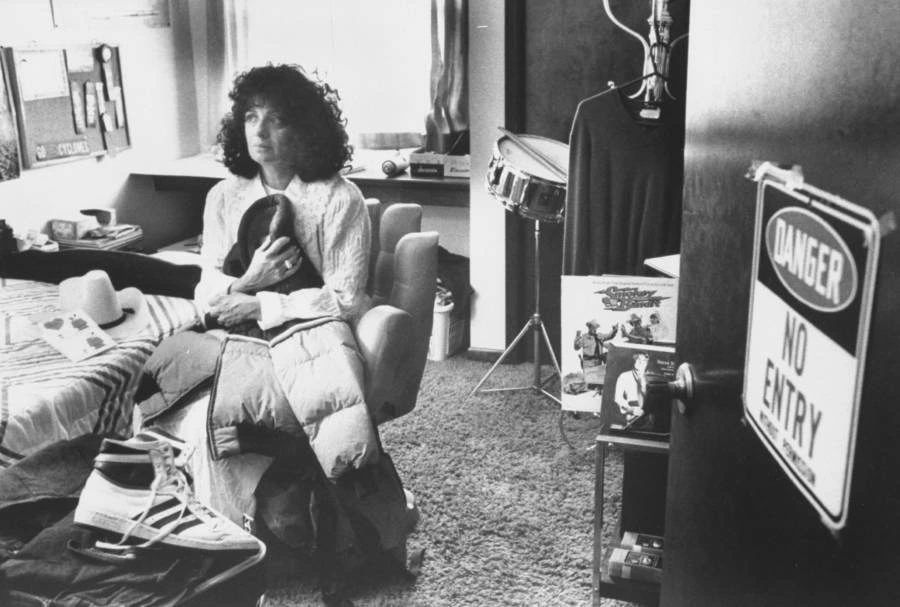

His mother, Noreen Gosch and father, John Gosch, often said he was the kind of kid who didn’t need to be reminded twice to do something.

Every morning, Johnny would wake up early to deliver newspapers for The Des Moines Register. He usually brought along his small dachshund, Gretchen and sometimes his dad would help with the route. But on that Sunday morning, Johnny decided to go alone. That decision would become the turning point of the entire story.

The Morning He Disappeared

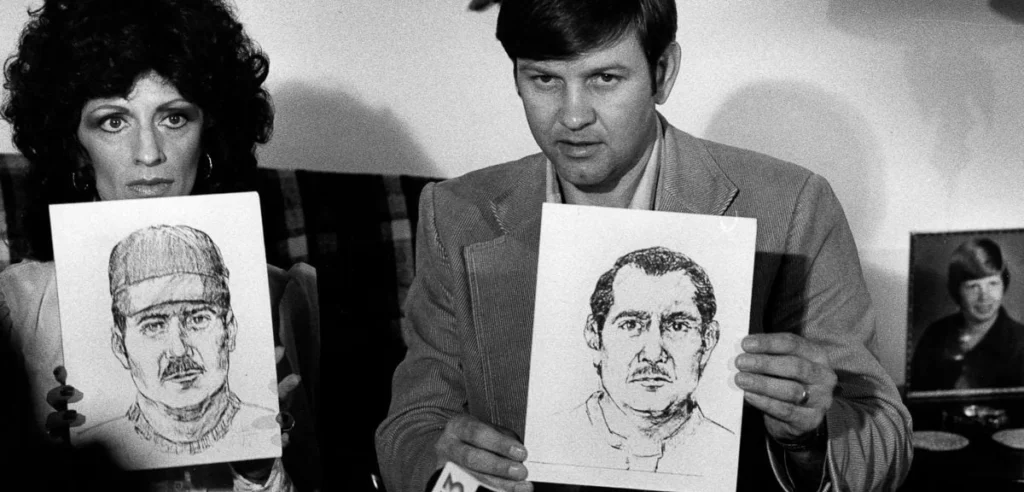

Between 6 and 7 a.m., Johnny left home with his red wagon filled with newspapers. A few other paperboys saw him that morning at the newspaper drop. Witnesses later said Johnny had been talking with a stocky man driving a blue two-toned car, according to Our Quad Cities.

One of those witnesses, a paperboy named Mike, saw Johnny chatting with the man, who seemed out of place that early in the morning. Another witness, John Rossi, said he saw the same man and found the situation odd.

According to Rossi, the man was asking Johnny for directions. Johnny even asked Rossi to help, saying something like, “This guy’s lost.” Rossi tried to memorize the license plate number. Later, under hypnosis, he remembered several digits and that it was from Warren County, Iowa.

After that, Johnny continued his route — but he was being followed. A neighbor soon heard a car door slam and saw a silver Ford Fairmont speeding away from the area. Moments later, Johnny’s wagon was found abandoned, still full of newspapers.

At home, customers began calling Johnny’s father, John Gosch, complaining that they hadn’t received their papers. Concerned, John went out to check and discovered the wagon two blocks from their house. But there was no sign of his son.

The Search for Johnny

The Gosch family immediately called the West Des Moines police. What followed became one of the most criticized parts of the entire case. Noreen later said officers took about 45 minutes to arrive.

Even more frustrating — police initially treated Johnny’s disappearance as a possible runaway case. At that time, Iowa had a policy that required waiting 72 hours before classifying someone as officially missing.

Noreen was furious. “The slow reaction and failure to take immediate action cost precious time that might have saved my son,” she said later.

That delay haunted her for decades. From that point on, she became relentless in pushing for change — not just for Johnny but for every child who went missing after him.

As the hours turned into days, it became clear Johnny hadn’t run away. His wagon, his dog and his earnings were all left behind. Police set up searches, volunteers combed fields and parks and the community put up flyers. But there were no solid leads.

In the following months, reports started to trickle in. Noreen said she received calls from people who thought they’d seen Johnny. One woman claimed she spotted a boy matching his description in Tulsa, Oklahoma, shouting for help before being pulled into a car by two men. Police couldn’t verify it, per Wikipedia.

Despite countless tips and witnesses, no suspects were ever charged. Over time, the case grew colder.

Private Investigators and New Theories

Noreen refused to give up. She hired private investigators, including retired NYPD detective Jim Rothstein and former FBI chief Ted Gunderson, to help her find answers. They uncovered theories about possible child trafficking rings but nothing could be proven.

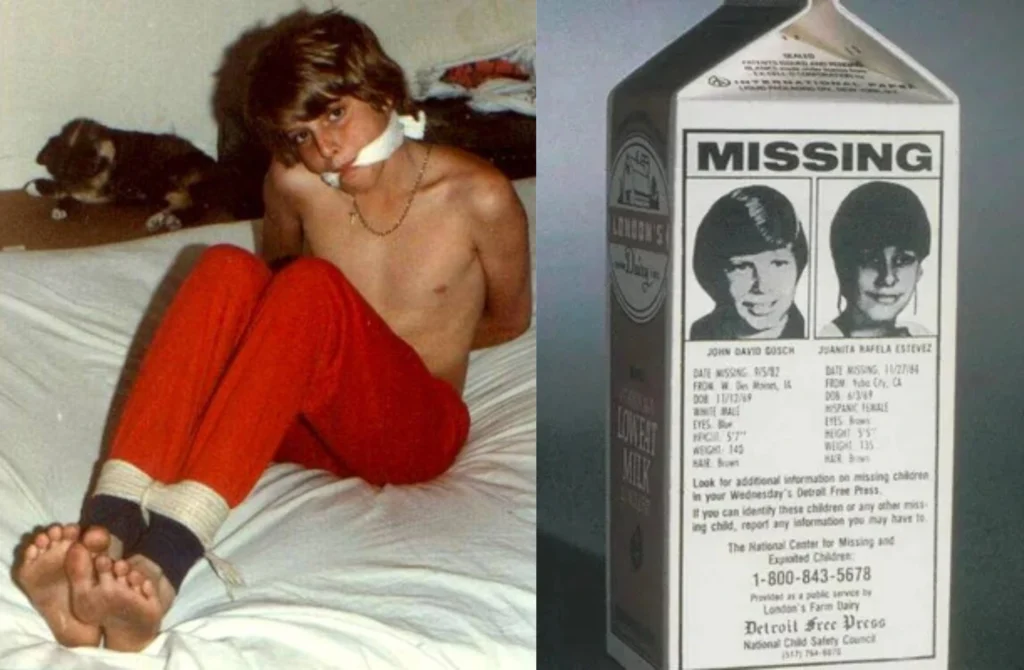

One thing did emerge from the case, though — Johnny Gosch’s face became one of the first to appear on milk cartons. The image of the smiling 12-year-old boy staring back from breakfast tables across America became a powerful symbol. It marked the start of a new movement. One focused on missing children, public awareness and accountability.

Two years after Johnny vanished, another paperboy, Eugene Martin, disappeared while delivering papers in Des Moines. Then, in 1986, Marc James Warren Allen also vanished. At first, reporters mistakenly called Allen a paperboy too but his family later corrected that.

Authorities never linked the three cases directly, but the similarities — young boys disappearing from the same area — were concerning. Noreen claimed that before Eugene Martin disappeared, a private investigator warned her another abduction might happen.

The 1985 Fraud Scheme

In 1985, the case took a strange turn. Noreen received a letter from Robert Herman Meier II, a 19-year-old from Michigan. He claimed to be a guard for an outlaw motorcycle gang supposedly involved in Johnny’s abduction. Meier said Johnny had been sold into a child slavery ring and demanded ransom money.

Desperate for answers, the Gosches sent $11,000. But then Meier asked for another $100,000, promising to bring Johnny home. It was all a scam. The FBI arrested Meier for wire fraud when he tried to flee to Canada. The hoax hurt the Gosch family deeply and it made future tips harder for law enforcement to take seriously.

One of the most controversial claims came years later. Noreen said that in March 1997, she woke up around 2:30 a.m. to a knock at her apartment door. When she opened it, she said her son was standing there — now a grown man — with another unidentified person beside him, the CNN reports.

According to Noreen, she recognized Johnny instantly. “He opened his shirt and showed me his birthmark,” she recalled. They talked for more than an hour, but Johnny was nervous, constantly looking at the man who had come with him. Noreen said he wouldn’t say where he was living or what had happened.

She described his appearance as different: long black hair, thin build, wearing jeans and a winter coat. After that night, she never saw him again. She later worked with the FBI to create a composite sketch based on his adult appearance which she shared in her 2000 book, Why Johnny Can’t Come Home.

Johnny’s father said he wasn’t sure whether to believe the story. Police could never confirm it and many still debate whether the man who visited her was really Johnny.

The Photos on Her Doorstep

In 2006, Noreen found disturbing photographs left outside her home. One of them, she said, showed a boy who looked like Johnny — bound and gagged. Others appeared to show boys in distress and one photo allegedly showed a man who might have been one of Johnny’s abusers.

When the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office in Florida investigated, they determined some photos were linked to an old child exploitation case from the 1970s — unrelated to Johnny. Authorities dismissed the photos as coincidences but Noreen wasn’t convinced. “I know what my son looks like,” she told reporters, insisting one of the boys in the photo was Johnny.

In 1989, Paul A. Bonacci, an inmate who claimed to have been part of a child exploitation ring, said he was forced to help in Johnny’s kidnapping. Bonacci described private details about Johnny — a birthmark, scars and a stammer — details that weren’t public.

Noreen met Bonacci and said she believed him. His lawyer, John DeCamp, backed him up, calling him credible. But police and the FBI didn’t. They said Bonacci’s story didn’t hold up and that his own siblings had confirmed he was home in Nebraska at the time of Johnny’s disappearance.

Still, Bonacci continued to insist he had met Johnny years later and that Johnny had visited him several times. Those claims only deepened the mystery.

National Change

Even without answers, Noreen refused to stay silent. She started the Johnny Gosch Foundation, dedicated to protecting children from predators and pushing for stronger laws. Her advocacy led to the Johnny Gosch Bill, passed in Iowa in 1984 which required police to respond immediately to missing child reports instead of waiting 72 hours. Other states soon followed.

In August 1984, Noreen testified before the U.S. Senate about organized crime and child exploitation. She even received death threats afterward. Later that year, she attended the White House dedication of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, invited personally by President Ronald Reagan — a recognition of her fight for reform.

Over the years, the case continued to draw attention. In 2014, the documentary “Who Took Johnny” explored every theory and interview, bringing the mystery to a new generation. It featured extensive interviews with Noreen and reexamined the strange clues that still lingered decades later.

Today, more than 40 years after that September morning, no one has ever been arrested and Johnny’s fate remains unknown. But his case changed the country. It changed how police respond, how parents protect and how the public looks at a missing child’s face on a screen or carton.

Johnny Gosch’s disappearance started as one family’s nightmare. It ended up reshaping an entire nation’s awareness of what it means when a child goes missing and how fast every second can matter.

Let’s dig into how police negligence impacts missing cases.

How Police Negligence Can Affect Missing Person Investigations

When someone disappears, time moves differently. Minutes feel like hours. Families call, neighbors look and police — well, they’re supposed to act fast. But what happens when they don’t? When hesitation, paperwork or poor judgment replace urgency?

Police negligence doesn’t just delay justice; it can erase it. Across the U.S., there are painful examples where slow or careless law enforcement responses cost precious time — sometimes, lives.

Why Police Response Matters

When a person, especially a child or vulnerable adult goes missing, the first line of defense is law enforcement. They’re the ones who issue alerts, organize searches and connect clues before the trail goes cold.

Experts often say the “golden hours” right after a disappearance are the most important. Quick action can mean a rescue; delay can mean a lifetime of not knowing.

But not all departments treat these moments with the same urgency. Negligence can creep in quietly — a report brushed off, a lead ignored or an assumption that “they’ll turn up.” Sometimes, it’s misclassification.

Police mark a disappearance as a runaway or misunderstanding, rather than a potential abduction. Other times, it’s lack of follow-up, poor communication or even missing paperwork.

A pattern that has surfaced in several U.S. cities shows deeper cracks. Investigative journalists in Chicago, for instance, found that nearly half of police records for missing persons had missing or incorrect information about when officers arrived to investigate.

Some reports were denied outright — illegally. Others sat unprocessed for days. Families, especially those from minority backgrounds, said they felt invisible. One mother told reporters her daughter’s disappearance “didn’t seem to matter until it was too late.”

When the people who are supposed to protect lose urgency, the damage runs deep. Trust erodes, families start hiring private investigators, communities grow suspicious and somewhere, a missing person slips further from being found.

What Happens When Police Drop the Ball

When police hesitate, the effects aren’t just bureaucratic — they’re life-altering. Delayed responses mean evidence vanishes: tire tracks fade, witnesses forget, security footage is erased. The early window for locating someone safely narrows.

One of the biggest mistakes officers make is assuming a person has run away without verifying it. In cases involving children or teenagers, this assumption has proven devastating. Critical searches that could have started immediately often don’t begin until days later. By then, leads have dried up.

Families describe the same experience over and over again: “They didn’t believe us,” “They told me to wait,” “They said she probably went off with friends.” Behind those words are missed phone traces, delayed BOLO alerts and no one knocking on doors until the trail’s cold.

Police negligence also increases risk. When law enforcement doesn’t act quickly, it sends an unintended message — that there’s little consequence. Offenders who abduct, harm or exploit others feel emboldened when they see cases ignored or dismissed.

Negligence also appears in the way police handle potential danger before a person vanishes. Victims of stalking or domestic violence often reach out for help before they go missing. Yet, repeated complaints are brushed off. The pattern is clear — the system reacts after a tragedy not before.

Systemic Patterns Behind Delays

Researchers and advocacy groups that study this stuff say police sometimes mess up these cases because of things like bad training, bias or just not making them a big enough priority. Families of missing people say it often feels like when they first call for help, no one really listens. It’s like hitting a wall instead of getting help.

In Chicago, investigations into the police department’s handling of missing persons revealed consistent mismanagement, particularly in cases involving Black youth.

Some reports were never entered into the system. Others were delayed by hours — sometimes days. Families described being left in the dark, calling precincts over and over just to be told “we’re working on it.”

Across the country, the same story repeats with different names and faces. Police departments overwhelmed by staffing shortages, untrained in child abduction protocol or dismissive of families’ urgency. In many rural areas, officers simply don’t have the specialized training to identify signs of abduction or trafficking early on.

And yet, these early hours define everything that comes next.

Legal Loopholes and Accountability Problems

When a police department mishandles a case, families often want to sue — to hold someone accountable for the mistakes. But the law rarely makes that easy. Courts tend to draw a firm line between what’s called a public duty (protecting everyone) and a private duty (protecting a specific person).

That means unless police specifically took charge of someone’s safety and then failed, it’s nearly impossible to prove negligence in court. One famous example is the UK’s Hill case, where judges ruled that police owe a duty to the public at large, not to any individual victim.

The reasoning was that if every investigative failure could lead to a lawsuit, officers might hesitate to act or allocate resources.

This same logic often shields American police departments. Even when investigative failures are obvious — when leads are ignored or reports are misfiled — families rarely win in court.

Legal experts call it “practical immunity.” There are exceptions but they’re rare. If an officer directly assures a family “I’ll take care of it” or takes control of a situation and fails, then liability might apply. Otherwise, the system closes ranks.

To families who’ve lost loved ones, that sounds like legal language for “no accountability.”

Why Risk Assessment Matters So Much

Behind many stories of police negligence lies a simple failure: not recognizing danger soon enough. Risk assessment — evaluating how likely it is that someone’s in immediate harm — is at the heart of every investigation. But in too many cases, police underestimate the threat.

Victims who reported stalking, domestic violence or prior threats often end up missing or harmed after police dismissed their fears. Officers sometimes downplay non-physical threats like digital harassment or they fail to treat protection order violations seriously. When that happens, danger escalates and sometimes, it ends in tragedy.

Part of the problem comes from outdated training. Another part is bias — assumptions about which cases are “serious” or which people are “credible.” Both can turn life-and-death situations into paperwork.

The Human Cost of Delay

For families, the waiting is torture. They replay every phone call, every unanswered question, every moment when someone could have done more.

Police negligence doesn’t just affect outcomes — it changes lives. Parents and siblings often end up running their own investigations, crowdfunding for billboards or combing through records themselves.

That loss of trust has a ripple effect, when people stop believing police will act, they hesitate to report future disappearances and that hesitation can make communities less safe overall.

Why Laws Still Protect Police

Even though more people are talking about the issue, the law still gives police a lot of freedom in how they handle cases. Courts usually don’t step in to question their choices — like who they search for, when or how. The idea is that forcing strict rules on police could mess with resources and slow down other investigations.

But for families those legal protections feel like walls. While they understand the challenges officers face, many believe there must be a clearer standard of care. Something that defines how quickly and thoroughly police should respond when someone vanishes.

Police negligence in missing person cases isn’t just about mistakes. It’s about a culture that sometimes forgets the urgency of a human life. While some departments have made real progress with new training, technology and early alert systems, others still lag behind.

Experts say the solution isn’t just better laws; it’s better accountability. Departments need independent review boards, transparent data on response times and policies that treat every disappearance as a potential emergency until proven otherwise.

Families shouldn’t have to fight for urgency. Every missing person deserves more than a case file and a clock ticking down.