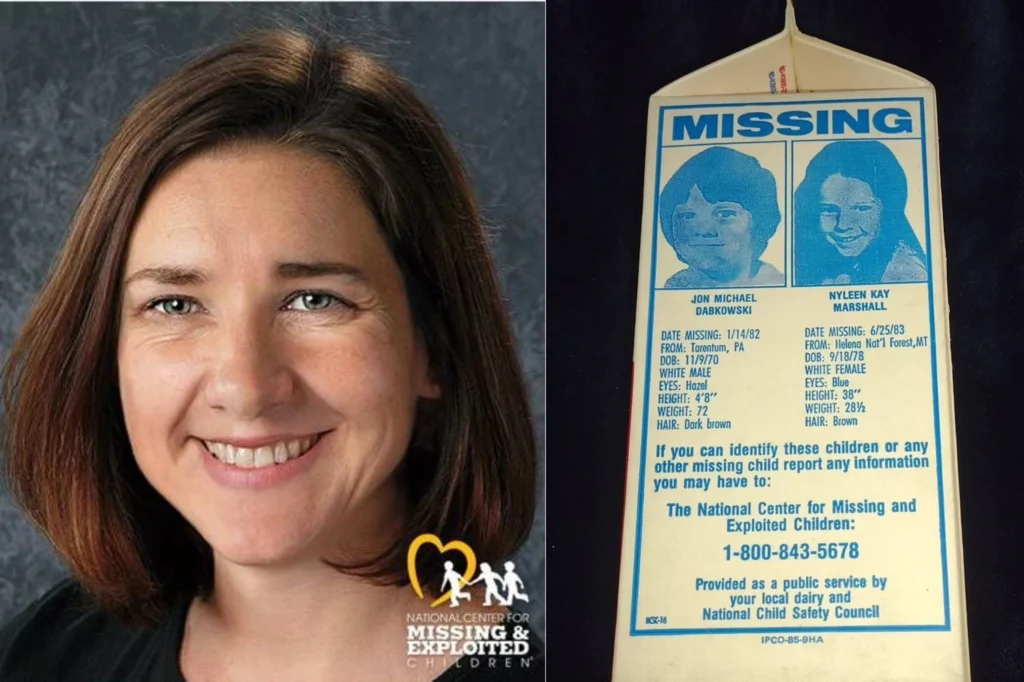

On a summer afternoon in 1983, four-year-old Nyleen Kay Marshall vanished without a trace in the Helena National Forest. She had been playing near Maupin Creek during a family outing when, within seconds, she was gone.

Despite one of the largest search operations in Montana’s history, not a single trace of her was ever recovered. More than forty years later, the case remains unsolved.

Early Life

Nyleen was born on September 18, 1978, in Orange, California. Her birth name was Nyleen Kay Briscoe, though she later took her stepfather’s last name, Marshall. She was just four years old when she disappeared.

By the early 1980s, Nyleen lived near Clancy, Montana, with her mother Nancy Marshall and her stepfather Kim Marshall. Her family was active in outdoor activities and had a particular connection to local radio clubs.

The day of the disappearance, they were participating in an amateur radio “Field Day,” a preparedness exercise where operators practiced setting up emergency communication systems.

For the Marshalls, this outing was meant to be a simple summer picnic—time with family and friends, surrounded by the Elkhorn Mountains’ rugged beauty. What happened instead became one of Montana’s most unsettling mysteries.

June 25, 1983 – The Day Everything Changed

The afternoon started like any other family event. Children splashed near the creek and played around the beaver dams. Adults busied themselves with food, conversations and radio equipment.

Around 4:00 p.m., Nyleen was last seen by a group of children near the water. They walked a few steps ahead and when they turned back, she was gone. At first, no one panicked. The assumption was that she had wandered off a short distance. But within minutes, as calls of her name went unanswered, panic spread.

Her parents and other adults scoured the area before alerting law enforcement. Soon after, the search grew into one of the largest Montana had ever seen.

Hundreds of people showed up to help look for Nyleen, including police, forest workers and even the National Guard. They searched for miles through the thick woods, search dogs tried to track her smell and divers went into the ponds and caves near the beaver dams.

Rescue crews dismantled parts of the dams to see if Nyleen had been trapped. Helicopters hovered over the dense canopy while ground searchers combed through brush and rocky slopes.

Despite days of intensive searching, there wasn’t a single footprint, scrap of clothing or sign that Nyleen had ever left that creek bed.

Sheriff Tom Dawn summed up the frustration years later, saying, “This case has been baffling for decades and continues to weigh heavily on the community.”

The Jogging Suit Stranger

As investigators dug deeper, unsettling witness accounts emerged. Several children reported seeing a man in a jogging suit near the area before Nyleen disappeared. Some even claimed he spoke to her, telling her to “follow the shadow.”

No one knew who this man was, his description was vague and no one could track him down. Whether he was connected to Nyleen’s disappearance or just a stranger passing through the woods remains unknown but his presence added an ominous layer to the story.

Like in many missing child cases suspicion first fell on those closest to her. Investigators questioned family members, including Kim Marshall, her stepfather. He was considered a person of interest at one point but was never charged with any crime. No evidence tied him to her disappearance.

With no physical clues and no clear suspects, the case seemed to stall. But then, two years later, the story took an even stranger turn.

Phone Calls and Letters From “The Abductor”

In late 1985, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children and other organizations began receiving phone calls from an unidentified man. He also contacted Nyleen’s family.

The calls were traced to phone booths in Edgerton, Wisconsin. Each time authorities tried to intervene, the caller stopped.

Soon, a typewritten letter arrived. It contained details about Nyleen’s case that had never been made public, suggesting the writer had insider knowledge.

In the letter, the man claimed he had taken a girl named Kay from Elkhorn Park near Helena. He said he homeschooled her, traveled with her across the U.S., Canada and even Great Britain. According to him, she was happy and he “loved her” but could not “let her go.”

Authorities believed the letter’s tone and content indicated sexual abuse though nothing was ever proven. His identity has never been discovered and the possibility that Nyleen was alive but being held by this anonymous man only deepened the anguish for her family.

The letter to Nyleen’s parents read in part:

“I picked “KAY” up on the road in the Elkhorn Park area between Helena and Boulder. She was crying and frightened and as I held her she was shaking and I decided that I would keep her and love her. I took her home with me.

I have a nice investment income and I can work at home so I care for her myself all the time. I teach her at home and she likes to go with me when I travel. She would gladly recount to you trips to San Francisco, New York, Oklahoma City, New Orleans, Nashville, Chicago, Puerto Rico and Canada. We were even in Britain for a month last year and she loved it. Nobody questions passports.

Her hair is short and curly now and she has really grown. She is about 45 inches and around 50 pounds. She has all four of her permanent upper and two of her lower incisors at this time. She takes a bath and brushes her teeth every day.

I give her medicine from the bathroom every morning. It is actually a spoonful of my semen. It doesn’t affect her physically. I have NEVER “molested” her in any other way.

She is a sweet little girl and it is because of how much I have grown to love her that I realize how much her family must miss her. But she has adjusted and seems happy. She trusts me and isn’t afraid. We play [sic] alot and she laughs when we clown around. She smiles and acts coy when I tease her. She giggles when we snuggle and hugs me sometimes for no apparent reason. I love her and I have her. I just can’t let her go.”

False Confessions and Frustration

The years that followed brought more confusion. One man, known only as Wilson, confessed to killing a woman in Great Falls and also claimed responsibility for Nyleen’s death. He even led police into the Elkhorn Mountains, pointing out supposed burial sites.

But nothing was found. His story kept shifting and authorities eventually declared him mentally unstable. Lewis and Clark County Attorney Mike McGrath later remarked, “His confession needed to be taken with a grain of salt due to the fact his story kept changing.”

Cases like this drain resources and renew grief while ultimately offering no answers.

By 1994, the Marshall family had relocated from Montana to Japan. The following year, in 1995, Nancy Marshall was murdered while in Mexico.

A Possible Sighting in New Orleans

In 1997, a nurse at a hospital in New Orleans reported what could have been a sighting of Nyleen. The nurse said a young woman around nineteen years old, came in with a man seeking to be admitted to give birth. The woman called herself “Helena” and said she thought her mother’s name might have been Nyleen.

She also claimed she grew up in another country even though she spoke without an accent. When hospital staff tried to ask the pair more questions about their identities and medical history, they suddenly left the building.

The strange encounter was reported to police but no further evidence was found to confirm who the young woman was.

Still No Answers

Decades have passed, but the disappearance of Nyleen Kay Marshall is still open. The Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office continues to investigate and urges anyone with information to call them.

The case is officially classified as a non-family abduction, ruling out theories that she simply wandered away or was accidentally lost in the wilderness.

Her story has appeared on TV shows, including Unsolved Mysteries and has been featured in true-crime discussions across the internet. Each retelling brings back the same unanswered questions: Who was the man in the jogging suit? Who wrote those letters? And most painfully—what really happened to Nyleen?

Television host Nancy Grace once reflected on the case, saying, “Cases like Nyleen’s remind us of the fragility of childhood and the haunting nature of the unknown.”

Today, more than forty years later, the mystery lingers in the Elkhorn Mountains. Families still gather in those forests, and children still play by Maupin Creek. But the shadow of June 25, 1983, remains.

Let’s dig into the legal side of non-family child abduction.

Legal Consequences of Non-Family Child Abduction.

Non-family child abduction. The phrase itself sounds chilling and for good reason. It describes one of the darkest crimes a stranger—or even a distant acquaintance—can commit: taking a child who isn’t theirs, with no legal right or authority.

In the United States, law enforcement treats it with zero tolerance. Prosecutors, too. And the penalties are some of the harshest in the criminal code.

But what exactly happens when someone commits this crime? How do the courts see it? And what kind of punishment follows? To understand, you have to look at the laws, the penalties and the way investigators scramble to respond in those first terrifying hours.

Defining the Crime

At its core, non-family abduction is a branch of kidnapping law. Every state defines it slightly differently but the heart of it remains the same: the unlawful taking or holding of a child by someone outside the family circle.

No custody dispute here, no messy divorce fights—this is the stranger in a park, the neighbor with no rights or even the so-called “family friend” who has no legal authority to remove a child.

Courts often file it under aggravated kidnapping, because the victim is a child. The idea is simple: children are especially vulnerable and the law is built to reflect that. “When the victim is a minor, the state elevates the charge automatically,” explained a former prosecutor. “It means heavier sentences and fewer chances for leniency.”

And if the abduction jumps state lines, the whole case escalates instantly to the federal level. That’s when the Federal Kidnapping Act kicks in, a law that’s been around since the Lindbergh baby case of 1932. Once the borders are crossed, the FBI steps in and the stakes rise.

How the Charges Stack Up

So, what happens to someone caught in this crime? In short: they’re almost guaranteed to face felony kidnapping charges. That’s not just years behind bars—it’s decades.

Sentencing depends on what else happened during the abduction. If the child was harmed, threatened or exploited, prosecutors pile on additional charges: assault, child abuse, sexual assault, unlawful restraint. Each one can add years to a sentence. And in many states, a conviction automatically lands the offender on the sex offender registry—even if there wasn’t a proven sexual element.

According to federal law, someone convicted of crossing borders with a kidnapped child can face life imprisonment. State penalties aren’t light either. California, for instance, sets a baseline of five years for kidnapping but pushes it to life in prison if the victim is under 14.

Texas has similar statutes, calling it “aggravated kidnapping” with a punishment range of five to 99 years.

This isn’t about slaps on the wrist. Courts make sure of that.

The Race Against Time

Law enforcement sees these cases as a ticking clock. The first few hours are critical. When a child is reported missing and suspicion points to a non-family abduction, the response is urgent and wide-reaching.

Amber Alerts blast across highways, cell phones and news outlets. Search teams move quickly, combing parks, homes, cars and even airports. The FBI often joins in if there’s any hint the child could be moved across state lines. “It’s an all-hands effort,” former FBI agent Clint Van Zandt said, “Every tool we have comes out.”

Courts can also step in early. Emergency custody orders, immediate warrants, even federal subpoenas—anything that can help investigators move faster. The law is structured to treat every hour like gold in these situations.

What Convicted Offenders Face

If someone is convicted of non-family child abduction, the consequences follow them long after prison.

First, there’s the time. Sentences can stretch from ten years to life depending on aggravating factors. Then, fines and restitution payments—money ordered to support the victim or the victim’s family—pile on.

Civil rights can be stripped too: voting restrictions, loss of gun ownership and permanent bans from working with children.

In many cases, the stigma doesn’t end with release. Registration as a sex offender is common, forcing offenders to report their addresses, jobs and travel plans to law enforcement for life. For non-citizens, deportation is almost certain.

“This is a crime where freedom is not returned in full, even after the sentence,” noted Professor Wayne Logan. “The legal and social consequences extend permanently.”

It’s important to distinguish this from parental abduction. When a parent unlawfully takes a child during a custody dispute, it’s still a crime but the law treats it differently. Courts often focus on family law remedies and sentencing tends to be lighter—though not always.

With non-family cases, however, the threat is considered greater. There’s no blood tie, no custody issue, no parental bond. Instead, prosecutors assume higher risk: harm, exploitation, trafficking. That’s why the system reserves its harshest punishments for these offenders.

International Complications

Sometimes, abductions cross more than just state borders. International cases add a thick layer of legal red tape.

The U.S. is part of the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, which creates a process for returning children taken across countries, usually in parental custody disputes.

For parental abductions, the U.S. relies on 18 U.S.C. § 1204, which makes it a federal crime to take or keep a child outside the country to obstruct parental rights. In cases of non-family abductions, authorities instead turn to broader laws such as 18 U.S.C. § 1201, the federal kidnapping statute.

If an offender manages to cross into Canada, Mexico or overseas, extradition becomes the next battle. Treaties, international courts and diplomatic negotiations come into play. “It’s slow and painful,” says attorney Patricia Apy. “But the law is clear—these offenders cannot hide abroad.”

The Hard Part: Prosecution

Even with strong laws, trials can be difficult. Evidence isn’t always clean. Kids might be too scared or hurt to talk in front of everyone and sometimes nobody actually saw what happened. That’s when police and lawyers have to lean on phone records, cameras, or experts, to try and piece the story together.

False leads complicate things too. Over the years, law enforcement has been forced to waste valuable time on hoaxes, fabricated confessions or people inserting themselves into cases for attention. Prosecutors know these distractions delay justice.

Yet, despite the challenges, most jurisdictions push abduction cases as far as they can. Juries are rarely sympathetic to offenders. And judges often impose the highest sentences available.

Non-family child abduction is more than a legal category—it’s a crime that can tear whole families apart and make people in a town feel unsafe for years. When this kind of crime happens, the rules are really strict. The punishments are some of the hardest you can get and that makes sense because it’s about protecting kids.

Every time a case hits the news, it’s a reminder that the system is built to respond fast, prosecute aggressively and punish heavily. The justice system, for all its flaws, treats this crime as the crisis it is.

And maybe that’s the only part that brings a small sense of reassurance: when it comes to a child being taken by a stranger, the law doesn’t hold back.