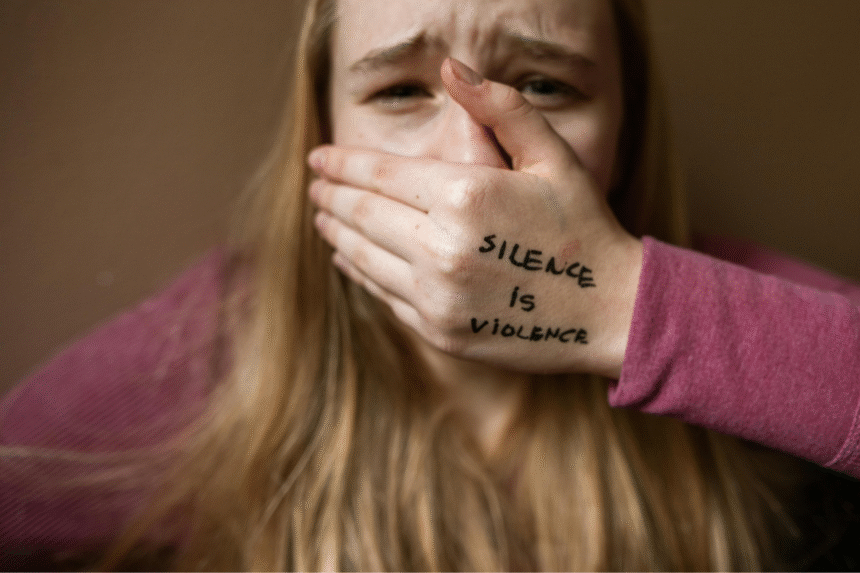

On a quiet Tuesday morning in a county courthouse, Mikasa, a young mother clutched a stack of papers, waiting for her case to be called. She wasn’t facing criminal charges or a civil dispute over money. She was asking for protection from the man she once trusted most. Her petition was for a restraining order — a piece of paper from the court that could help keep her safe from harm.

Stories like hers unfold every day across the world. Domestic abuse, in its many forms, affects millions of people and restraining orders are one of the most visible tools courts use to respond. These orders don’t stop abuse on their own but they create a clear legal boundary, a line that, if crossed, triggers consequences.

“Restraining orders are a survivor’s first line of defense,” says Marissa Boyd, a domestic violence advocate with Legal Aid of Northwest Texas. “It’s not a cure-all, but it tells the abuser, ‘the law is watching you now.’”

What Exactly Is a Restraining Order?

At its core, a restraining order — often called a protective order — is a court mandate that tells an abuser to stay away, stop contacting or cease harassing a victim. While laws vary by jurisdiction, the principle is the same: it gives survivors breathing space and empowers law enforcement to act if the abuser ignores the order.

The U.S. Department of Justice defines protective orders as “civil court orders designed to prevent further violence, harassment or contact by an abusive party.” In cases of domestic abuse, these orders can be filed against spouses, ex-partners, cohabitants, family members or even in-laws.

It’s worth noting that domestic abuse is rarely one-dimensional. While many imagine bruises and black eyes, abuse can also appear as intimidation, financial control, stalking or psychological torment. Courts recognize this, and so restraining orders now cover many kinds of harmful behavior — even things like threatening text messages or trying to control someone’s life.

The Many Faces of Abuse

Ask survivors and they’ll tell you: abuse doesn’t always announce itself with violence.

Some describe being isolated from friends, others having their bank accounts drained or monitored. Emotional manipulation, insults or constant monitoring through phone tracking apps all count as abuse.

According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, one in four women and one in nine men experience severe intimate partner violence in their lifetime. These statistics show that abuse is common and can happen in many different ways. Restraining orders are designed to respond to this complexity by offering protections that go beyond just “stay away.”

The Process: From Petition to Courtroom

Filing for a restraining order is often described by survivors as both empowering and intimidating. The journey usually begins with paperwork at a local courthouse.

First, the survivor explains in writing the abuse they’ve endured. Judges may issue an emergency or temporary restraining order (TRO) immediately, sometimes the very same day. TROs usually last until a full court hearing is held.

Next comes the difficult step of serving the abuser. This makes sure they know about the order and the court date. Usually, the police or another trained person delivers these papers.

Finally, both sides appear in court. Survivors may testify, present text messages, photos or witness statements. The accused can defend themselves. After hearing evidence, the judge decides whether to issue a longer-term order which might last for months or even years.

“It’s a nerve-wracking process,” recalls Jennifer, a survivor in Ohio who obtained a restraining order against her ex-husband. “You’re reliving the worst moments of your life in front of strangers, but in the end, it was worth it. I walked out feeling like the law was finally on my side.”

What Restraining Orders Can Do

The protections available depend on what the survivor requests and what the court finds appropriate. Typical provisions include:

- Ordering the abuser to stay a specific distance away from the survivor’s home, job or school

- Banning all contact — no calls, texts, emails or messages through friends

- Removing the abuser from a shared residence

- Suspending the right to own or carry firearms

- Establishing child custody or visitation rules to keep children safe

- Financial support such as temporary spousal or child support

Some states even allow courts to include pets in protective orders, recognizing that abusers sometimes harm animals to intimidate victims.

“The goal isn’t just distance,” explains family law attorney Rachel Collins. “It’s about restoring control to the survivor. Every detail — from who gets the car to who picks up the kids — matters when safety is on the line.”

The Enforcement Challenge

A restraining order is strong as a rule on paper, but making it work in real life can be hard. Police departments are tasked with responding to violations but survivors often face delays or skepticism when reporting breaches.

Research published in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence shows that while restraining orders reduce future abuse in many cases, their effectiveness depends heavily on law enforcement’s response and the survivor’s willingness to report violations.

“Some survivors are terrified to call the police,” says Boyd, the advocate. “They fear retaliation. And in smaller towns, officers may not always treat a violation with urgency. That gap can be deadly.”

Beyond the Standard Restraining Order

Different jurisdictions have developed variations of restraining orders to address immediate threats.

In the U.K., for example, police can issue a Domestic Violence Protection Notice (DVPN), forcing an abuser to leave the home for up to 48 hours. Courts can then extend that with a Domestic Violence Protection Order (DVPO), which lasts up to 28 days.

In the U.S., survivors may also encounter terms like no-contact orders (often tied to criminal cases) or civil protection orders (filed in family court). In some cases, courts even issue restraining orders after a criminal trial ends in acquittal, recognizing that acquittal does not equal safety.

Firearms and High-Risk Cases

One of the most critical aspects of restraining orders in the USA involves firearms. Federal law prohibits abusers under active protective orders from possessing guns. This is not symbolic. Research from the American Journal of Public Health has found that access to firearms increases the risk of intimate partner homicide by 500 percent.

Still, loopholes remain. Not all states enforce gun surrender effectively and some abusers slip through the cracks. Survivors’ advocates argue this is one of the most urgent issues in domestic violence law.

How Long Do They Last?

Restraining orders can be temporary or long-term. Some expire after six months; others extend for several years. Survivors may petition for renewals if danger continues. Judges often balance the survivor’s need for protection with the legal principle of proportionality.

“Every case is different,” says Judge Linda Ramos of California’s Family Court. “We look at patterns of behavior, the level of threat and the likelihood of reoffending. Our goal is always to protect without overreaching.”

When Orders Are Violated

If an abuser violates the order, the survivor’s next step is clear: call the police. Violating a restraining order is a crime and can result in arrest, fines or jail. Survivors are encouraged to document incidents, save voicemails or texts and gather witnesses when possible.

Some survivors describe feeling frustrated when violations go unpunished. “He would text me from a blocked number,” recalls Maria, a survivor in New Jersey. “The police said they couldn’t trace it. It felt like he was always one step ahead.”

Not a Silver Bullet

Despite their importance, restraining orders are not foolproof. Abusers who are determined may ignore them and survivors sometimes continue to face danger. That’s why experts stress that protective orders should be part of a broader safety plan including counseling, shelters and community resources.

“Restraining orders save lives,” says Collins, the attorney. “But they work best when combined with support systems — safe housing, financial independence and social services. Otherwise, survivors may still feel trapped.”

The National Domestic Violence Hotline echoes this view, advising survivors to treat restraining orders as one tool among many.

For survivors like Mikasa waiting nervously in that courthouse, a restraining order is more than legal paperwork. It is a signal that the system sees their struggle and is prepared to intervene. While no court order can erase abuse, restraining orders carve out a legal line in the sand — one that, when enforced, can give survivors the time and space they need to rebuild their lives.