The story of Francine Hughes shocked America in 1977. On a cold March night, Francine set fire to the bed of her abusive ex-husband, James “Mickey” Hughes, while he slept. The flames consumed their Michigan home and ended his life.

What followed was a courtroom drama that introduced a new legal concept: “battered woman syndrome.” Her case forced the country to look at domestic abuse in a way it hadn’t before.

Growing Up and Falling in Love

Francine Moran Hughes was born on August 17, 1947, in Stockbridge, Michigan. Life wasn’t easy. Her father, an alcoholic farmhand, was violent and home was far from safe. Francine was named after a French musician but her childhood didn’t leave much room for music or joy.

At sixteen, Francine dropped out of high school to marry James “Mickey” Hughes. She thought marriage would be her way out. Instead, it was a trap. Together they had four kids: Christie, Jimmy, Nicole, and Dana. But the young love didn’t last. Mickey was quick-tempered and violent.

By 1971, Francine divorced him but Mickey came back just months later. A bad car accident left him injured and Francine let him move back in, according to Wikipedia. She would later say she didn’t want to “hurt him more than he already had been” because of the crash. That act of pity marked the start of more years of abuse.

Trapped in Her Own Home

Mickey’s violence only escalated. Francine’s days were filled with fear. Mickey destroyed furniture, beat her regularly and even killed the family cat. He threatened her life constantly, making sure she felt she had no way out.

Police visits rarely changed anything. Officers would write reports but didn’t arrest Mickey unless they saw him hurt her themselves. Lee Atkinson, an assistant prosecutor involved in the case, later explained the frustrating cycle: “Are there bruises? Yes. Does she appear to have been abused? Yes. The police would file a report but they wouldn’t make an arrest.”

At the time, domestic violence was seen as a private matter, something to be handled quietly at home. That left Francine helpless.

One incident showed just how cruel Mickey could be. Francine recalled him smashing food, throwing trash on the floor and rubbing it into her hair while hitting her. This was her normal life.

The Breaking Point

On March 9, 1977, Francine came home after attending a secretarial course. She’d started taking classes to build a future for herself and her children. Mickey was furious. He was drunk, angry and ready to destroy anything in his path. He wouldn’t let her feed the kids and ordered her to burn her schoolbooks. When she hesitated, he attacked her, per History.

Police came after a call for help, but again, they didn’t arrest him because he hadn’t physically harmed her in their presence. The officer later testified that Mickey warned her, “It was all over” for her now that she had called the police.

That night Mickey forced Francine to clean up messes he made on purpose. He made her quit school and later raped her. After hours of abuse, Mickey passed out drunk in bed. Francine looked at him sleeping and felt trapped. If she stayed, she believed he’d kill her.

She made a decision. Francine got her children out of the house and into the car. She soaked Mickey’s bed with gasoline, struck a match and walked out. Flames tore through the home and Mickey never woke up. Francine didn’t run. She drove to the police station and confessed.

A Trial That Changed Everything

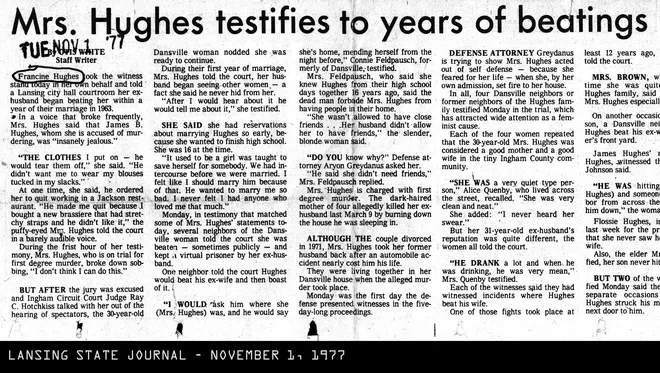

Francine’s trial in Lansing, Michigan, quickly made headlines. Reporters swarmed the courthouse and the case sparked debates about domestic abuse. Francine’s defense attorney knew he couldn’t argue self-defense—Mickey had been asleep when she killed him.

“Since Mickey was asleep, I didn’t believe I could persuade the jury that she was not guilty based on self-defense. So I utilized the temporary insanity defense,” he said.

The defense introduced a psychological concept that was barely known at the time: battered woman syndrome. Psychologist Lenore Walker had just begun to study how years of abuse trapped women in cycles of fear and helplessness. Francine’s case brought those findings into a courtroom for the first time.

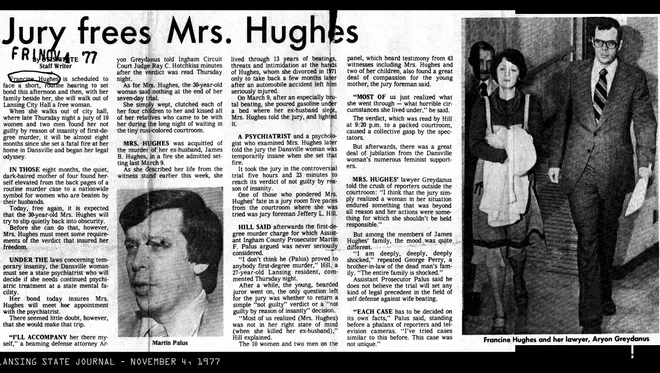

Prosecutors couldn’t ignore the abuse but they argued the killing was premeditated. The jury, however, saw something different. They decided Francine was not guilty because she was temporarily insane when it happened. This was a big deal. It was one of the first times a jury understood that years of abuse could push someone to act out of fear, not hatred.

A Nation Pays Attention

The trial made Francine Hughes a symbol, her story made people start talking about domestic violence, something many had ignored before.

People began asking why victims like Francine didn’t have help or safe places to go. Police actions were questioned and activists started fighting for more shelters, stronger laws and better training for officers to protect abuse victims.

Francine’s story was immortalized in Faith McNulty’s 1980 book The Burning Bed. The title became even more famous in 1984 when NBC aired a TV movie starring Farrah Fawcett as Francine.

More than 75 million people watched it. For many Americans it was the first time they saw what life inside an abusive home really looked like. The movie sparked a wave of activism, funding for shelters and a shift in how the justice system treated domestic violence.

Francine tried to move forward. She remarried in 1980, tying the knot with country musician Robert Wilson. She earned her license as a practical nurse and worked in nursing homes and classrooms, per The New York Times.

By all accounts, she lived a quiet life away from the spotlight that once defined her. Francine passed away on March 22, 2017, at 69, from complications of pneumonia.

Her son Jimmy later reflected on those dark years: “My mom would be battered and bloody, and police came then left without doing anything. She endured so much that it overshadowed the good times.”

Why This Case Still Matters

Francine’s case changed the way America thought about abuse victims who fought back. It exposed a justice system that often failed women. It also showed that self-defense didn’t always fit stories like hers where the danger wasn’t one moment but years of terror.

Her attorney’s use of “temporary insanity” opened the door for battered woman syndrome to be recognized in future cases.

This psychological defense has evolved over the years and many states now accept it in court. Francine’s trial pushed judges, lawyers and juries to see abuse survivors as more than just defendants.

Let’s take a closer look at the legal concepts around self-defense.

What If You Hit Back in a Domestic Violence Situation — Is It Still Self-Defense?

Imagine this: You’ve been pushed around, screamed at and hit so many times that fear feels normal. One day, you hit back. Maybe it’s in the heat of the moment, maybe you’re just trying to survive. But now, instead of just being a victim, you’re in a courtroom. Suddenly, everyone wants to know—was it self-defense or was it a crime?

In the U.S., this question doesn’t have a simple answer. Domestic violence cases where the victim fights back are complicated because every detail matters. What you felt in that moment, how serious the threat was and even what state you live in can change everything.

The Basics of Self-Defense

At its core, self-defense is about survival. The law says you can protect yourself if you’re in immediate danger but you can’t go overboard. The idea is simple: you can use enough force to stop the attack but not more than what’s needed.

“Self-defense is a legal doctrine that permits individuals to use reasonable force to protect themselves from imminent harm.” That word reasonable is important. Courts look at what a “reasonable person” would do in the same situation.

In domestic violence cases, this gets tricky. Abuse often happens behind closed doors, sometimes for years. Victims may feel trapped, believing that leaving or calling the police won’t save them. That changes how they react.

When the Law Protects You

Most states in the U.S. say victims of domestic violence can defend themselves. California’s laws are clear about this. According to California Penal Code §§ 692, 197, you can use force “when a person reasonably believes they are under imminent threat of bodily injury” but only if you use “no more force than necessary.”

If the threat is real and happening right now, you have the law on your side. But if you lash out because of a fear of something that might happen later, courts might not see that as self-defense.

And if you use too much force, like continuing to attack after the danger has passed, your defense could fall apart.

Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” law adds another layer. The law, in Florida Statutes § 776.012, says you don’t have to back away if you believe deadly force is needed “to prevent imminent death or great bodily harm.”

That sounds empowering but domestic cases are complicated. If both people live in the same home, the protections of the “Castle Doctrine” don’t always apply. You have to prove that you truly believed you were in immediate danger.

A Thin Line Between Protection and Retaliation

The hardest part of these cases is proving that the act was truly self-defense. Judges and juries want to know: was this about survival or revenge?

“Reasonable force” is the phrase you’ll hear over and over. It means exactly what it sounds like—your reaction has to match the threat. For example, if someone shoves you, pulling a weapon might seem excessive. But if you’re being choked or cornered, the same reaction might be justified.

The timing matters, too. Courts focus on imminence, meaning the threat had to be happening right then. If the person was asleep or had already walked away, your claim could collapse. This is one reason ongoing abuse cases are so difficult. Victims live in constant fear, and it’s hard to separate one attack from the next.

Defense lawyers often bring in experts to explain this. Psychologists talk about “battered woman syndrome,” a term that helps jurors understand why someone might feel trapped and why hitting back might feel like the only option.

State-by-State Differences

Every state handles these cases a little differently. In Oklahoma, for example, the law says that people living together can’t use the Castle Doctrine to justify force. Victims can still defend themselves, but they must prove that any force used was reasonable and necessary.

Colorado law is just as specific. It says the person’s belief in imminent danger must be both “subjectively genuine and objectively reasonable”. That means it’s not just about what you felt; the jury also has to see it as reasonable from the outside.

These details might sound small but they’re the difference between freedom and a prison sentence.

The Burden of Proof

Even if you were attacked, it’s on you to prove it was self-defense. You have to show proof that you were scared for your life. Police reports, witness statements, medical records and a history of abuse can all help.

Some states give more protection. Florida allows people to file for immunity if they meet the standards of lawful self-defense, shielding them from prosecution altogether. But that’s not a free pass. Judges still demand strong evidence.

The process can feel stacked against victims especially if there’s no physical proof of the abuse, judges and juries weigh the entire context including the history of abuse, timing of the defensive act and proportionality of force used.

The Role of Experts and Evidence

These days, experts can be a big help in court for cases like this. Psychologists tell the jury what life is really like for abuse victims—the fear, the control, and how trapped they feel. Lawyers use that to show why someone might honestly think their life’s in danger, even if it doesn’t look like it at the moment.

But experts can only do so much. Judges still want proof—photos, medical records, police calls and text messages. Restraining orders or past reports of abuse can strengthen a case but if you violated an order, that can hurt your claim.

Domestic violence cases aren’t just about what happened in one moment; they’re about years of fear and control. That’s what makes them so hard to judge. Some states have “Stand Your Ground” laws that remove the duty to retreat but those laws weren’t written with long-term abuse in mind.

Victims often say they feel like they’re on trial for surviving. The law gives you the right to defend yourself, but proving that you acted out of fear rather than revenge is tough.

The Takeaway

If you’re wondering whether hitting back in a domestic violence situation is legally self-defense, the answer is “it depends.” The danger has to be immediate, your actions have to be reasonable and the laws in your state play a huge role.

Cases like Francine Hughes’ prove that the justice system has come a long way in understanding abuse but there’s still a long way to go. Today, courts take domestic violence seriously but victims still have to fight to prove their fear was real and their actions were justified.

Knowing your state’s laws, keeping records and seeking help early can save lives and keep survivors from being punished for defending themselves.