If you ask historians about the most remarkable survival stories in American history, one name always rises to the top: Hugh Glass. His tale of grit, pain and sheer stubbornness in 1823 has become folklore on the frontier. “It seems incredible that a man in such a helpless condition should be able to reach a point of safety at such an immense distance,” wrote 19th-century chronicler James Hall, almost unable to believe what Glass accomplished.

The bare bones of the story are simple. A grizzly bear tore him apart in the wilds of South Dakota. His fellow trappers abandoned him. And against every reasonable expectation, he crawled, floated and stumbled for hundreds of miles to safety.

A Shadowy Beginning

Unlike many figures of the frontier, Hugh Glass didn’t leave behind neat records of his birth or family. Historians generally agree he was born around 1783 in Pennsylvania, likely to Scotch-Irish parents but beyond that, his youth is a mystery. There are rumors he may have spent time as a sailor or even lived briefly among pirates in the Gulf of Mexico, though evidence for that is thin.

What we do know is that by the 1820s, Glass had thrown himself into the fur trade—a booming but brutal business that drew tough men into uncharted territory. These were the mountain men, trappers who lived on the edge of survival, braving everything from violent storms to attacks by hostile tribes. “The fur trade was the Silicon Valley of its day,” explained historian Clay Landry in an interview. “It attracted risk-takers. And no one took bigger risks than men like Hugh Glass.”

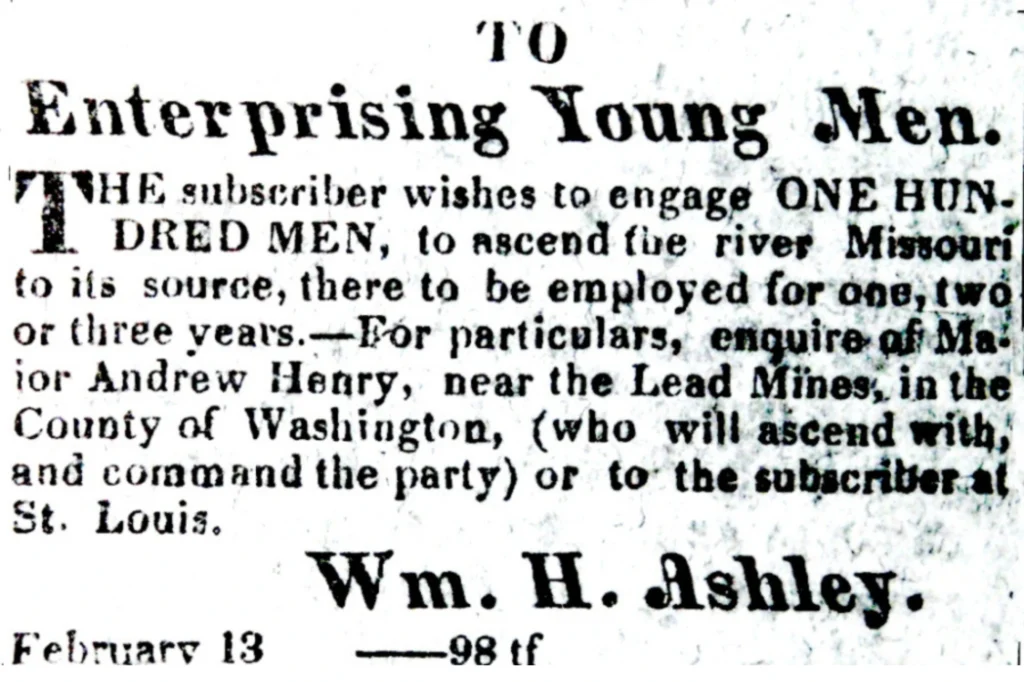

As stated by Britannica, in 1823, Glass signed on with General William Henry Ashley’s expedition. Ashley’s men, often called “Ashley’s Hundred,” were among the first to push deep into the Upper Missouri River region, covering parts of today’s Montana and South Dakota. They were searching for valuable beaver pelts which fueled the fashion for felt hats back in Europe.

The journey was already dangerous. Earlier that year, Ashley’s party had been attacked by the Arikara tribe, leaving more than a dozen men dead. Surviving that fight, Glass pressed on with the group as they moved along the Grand River. By summer, his luck would take an even darker turn.

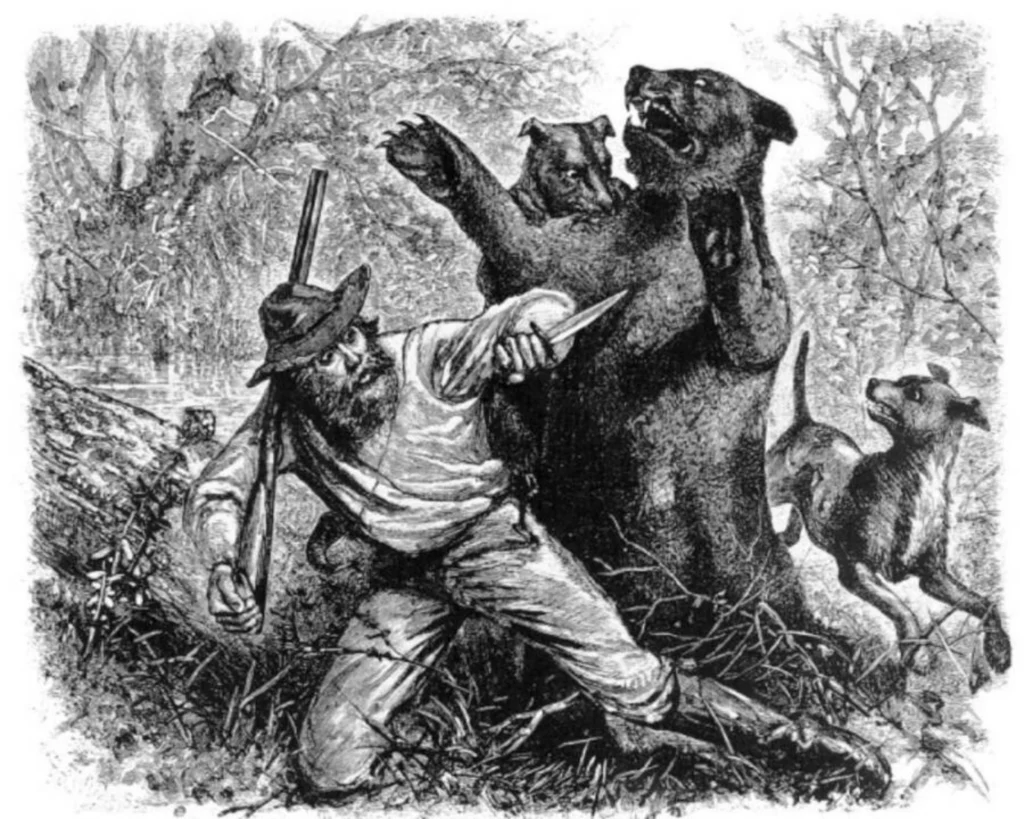

The Grizzly

The story begins with a single mistake. Somewhere near the Grand River, Glass wandered ahead of the group while scouting. Suddenly, he stumbled upon a mother grizzly bear and her two cubs. For a frontiersman, that was one of the worst encounters imaginable.

The bear charged. Accounts say she smashed him to the ground, biting and clawing with terrifying force. His scalp was ripped open, his ribs broken and his throat torn. Somehow, Glass fought back with his knife and gun, and fellow trappers rushed to finish the bear off. When the dust cleared, the animal was dead—but so was, in their minds, Hugh Glass.

His injuries were shocking. “By all accounts, he looked like a man already in the grave,” said author Jon T. Coleman, who has written about Glass’s ordeal. Laying in the wilderness, bleeding and half-conscious, he was expected to die within hours.

Ashley faced a dilemma. The party could not carry Glass for hundreds of miles across hostile terrain. Leaving him seemed cruel but slowing the expedition down might risk everyone’s lives. The compromise was that two men, John Fitzgerald and a young Jim Bridger would stay behind to care for him until the inevitable end, according to The Hollywood Reporter.

But death never came. Days passed and Glass clung stubbornly to life. Eventually, Fitzgerald and Bridger lost their nerve. Fearing attack by Native tribes and convinced Glass was doomed anyway, they abandoned him. Worse still, they took his rifle, knife and other gear—tools that meant the difference between survival and death.

For most men, that would have been the end. For Hugh Glass, it was the beginning.

The Crawl

Alone, unarmed and shredded by wounds, Glass began one of the most unlikely journeys in American history. At first, he could barely move. He dragged himself across the ground, inch by inch, surviving on insects, roots and whatever small creatures he could catch.

One story tells how he spotted wolves feeding on a freshly killed buffalo calf. He waited until they had their fill, then feasted on the carcass, eating enough meat to regain some strength. To keep infection from spreading, he allowed maggots to eat the dead flesh from his wounds—a gruesome but effective treatment.

Over the weeks, Glass’s crawl turned into a stagger. He floated part of the way downriver on a makeshift buffalo-hide raft, a trick he may have learned from Native tribes. Every mile was agony, yet every mile brought him closer to Fort Kiowa, the nearest trading post.

“He had one goal: to live long enough to take revenge on the men who left him,” said historian Clay Landry. That determination became the fuel that kept him moving.

Back From the Dead

By October 1823, against every expectation, Glass staggered into Fort Kiowa. Emaciated, scarred and limping, he was nonetheless alive. The other trappers could hardly believe it.

Glass immediately set out to track down Fitzgerald and Bridger. When he found Bridger, he saw only a terrified teenager, barely out of boyhood. Instead of killing him, Glass forgave him, saying he was too young to bear such guilt. Fitzgerald proved harder to reach. By then, he had joined the army, making him untouchable without risking Glass’s own life. Some accounts say Glass forgave him as well; others suggest he carried the bitterness quietly.

Either way, the man who was supposed to be dead had returned and his legend began to spread.

Surviving the bear attack did not tame Hugh Glass. If anything, it drove him deeper into the wilderness. He continued trapping and hunting across the Rockies, sometimes alone, sometimes with partners. He worked with companies like the American Fur Company and Columbia Fur Company, trading pelts and meat to supply remote forts.

His life remained violent and unpredictable. In one battle, he was struck by an arrow but lived through it. In another, he narrowly escaped death at the hands of Native tribes. Yet he kept returning to the wilderness.

“He was never a man to sit still,” wrote one early biographer. “The same spirit that carried him from the claws of the grizzly seemed to drive him onward, always further into the unknown.”

The End of the Trail

Hugh Glass’s final chapter came in 1833, a decade after the bear attack. While traveling near the Yellowstone River with fellow trappers Edward Rose and Hilain Menard, the group was ambushed by the Arikara tribe. This time, there was no escape. All three men were killed, as noted by Wikipedia.

Word of his death spread slowly, but his story was already larger than life. Fellow mountain men named landmarks after him such as Glass Bluffs on the Missouri River. Writers picked up his tale, turning it into frontier lore.

The line between fact and legend in Glass’s story has always been blurry. Early writers, like James Hall, admitted disbelief at his survival. Later stories added extra details or made guesses to fill in the parts that weren’t known. Even so, the core of the story has never been doubted: Hugh Glass endured what should have been certain death and lived to tell the tale.

Modern historians see his story as more than just a survival thriller. “Glass’s ordeal captures the brutality of the frontier,” Clay Landry observed. “It wasn’t just man versus nature. It was man versus hunger, isolation, betrayal—and still, somehow, hope.”

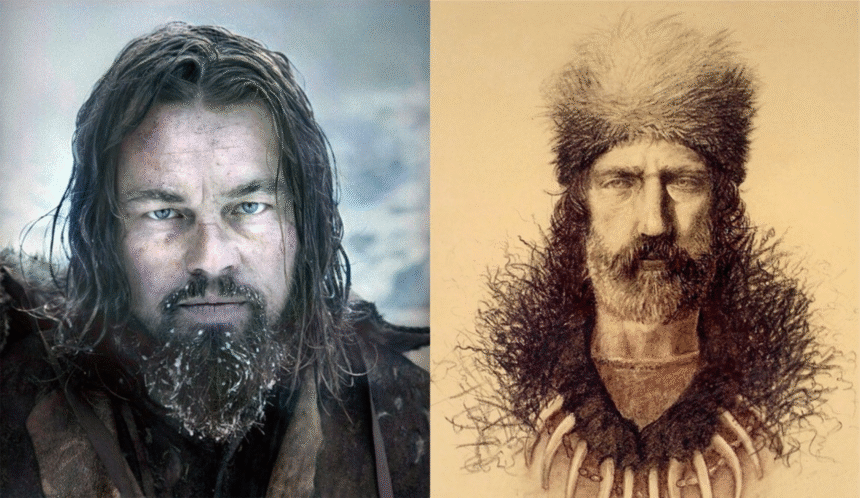

Today, his name is remembered not only in books but also in popular culture, most famously through the film The Revenant. Yet behind Hollywood’s dramatization is a real man who dragged himself out of the wilderness with nothing but willpower.