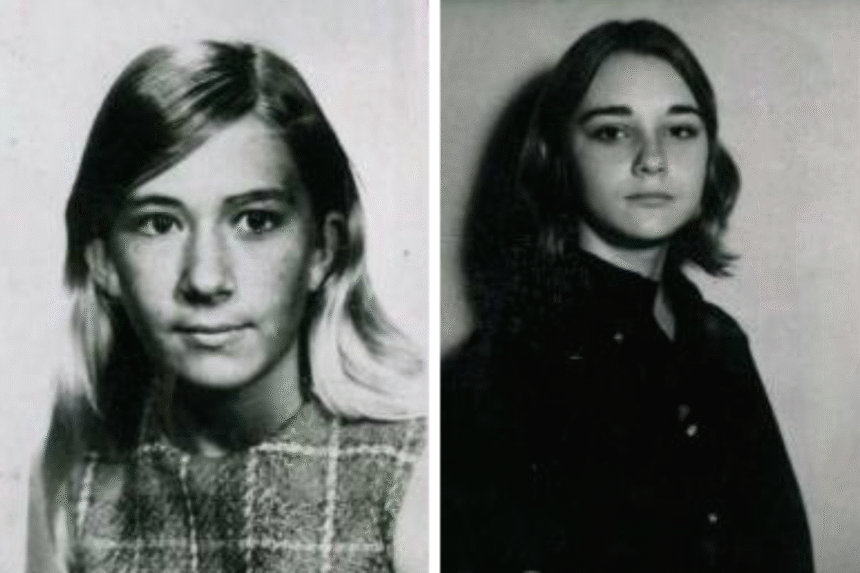

In 1971, two best friends left home for a carefree trip to the beach and never returned. What started as an ordinary outing for 14-year-old Rhonda Renee Johnson and 13-year-old Sharon Lynn Shaw turned into one of Texas’s most haunting murder mysteries, a case still debated half a century later.

A Day at the Beach That Ended in Horror

Rhonda and Sharon were inseparable. Both girls lived in Webster, Texas and had birthdays just a week apart—Rhonda born in December 1956, Sharon in August 1957. On August 4, 1971, they planned what should have been an ordinary summer adventure: a day by the water in Galveston. Witnesses spotted them walking along Seawall Boulevard that afternoon, laughing and carefree. That was the last time anyone saw them alive.

When the girls didn’t return home, their families quickly reported them missing. Police searches were launched but no trace of them surfaced for months. The case began to fade from headlines as the weeks passed.

A Grim Discovery

It wasn’t until January 3, 1972, that the mystery deepened in the most haunting way. Two young boys fishing in Clear Lake noticed something bobbing in the water that they thought was a ball. On closer inspection, they realized it was a human skull. Investigators were called in and six weeks later, searchers uncovered more remains in a nearby marsh.

Dental records confirmed the skull belonged to Sharon Shaw. A crucifix wrapped around her jaw was identified by her grieving mother. The other remains belonged to Rhonda Johnson, according to Unsolved Mysteries.

By then, the girls had been dead for months and the swampy conditions had stripped away almost all evidence of how they had died. Detectives had little to go on beyond the skeletal remains and a devastated community demanding answers.

A Break in the Case

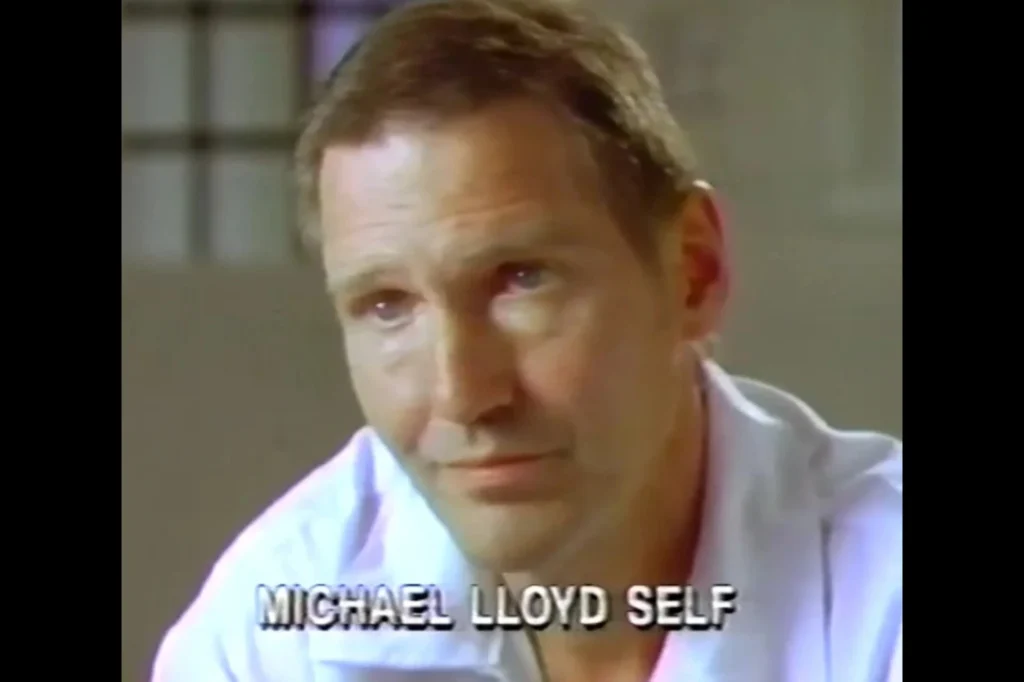

In May 1972, investigators got a lead from Galveston city councilman Glenn Price, who suggested looking into a local gas station worker named Michael Lloyd Self. Self was a quiet man in his early twenties, known around town but with no violent criminal record. He agreed to speak to police voluntarily. What followed would become one of the most disputed interrogations in Texas history.

Self later claimed that Galveston Police Chief Donald Morris physically assaulted him during questioning, hitting him with a nightstick and threatening to kill him if he didn’t confess. Under this pressure, Self signed a confession.

The written statement, however, was riddled with inconsistencies. He claimed he dumped the girls’ bodies in El Lago, a location far from where they were discovered. He also said he strangled them, though the remains showed no signs of strangulation.

Three days later, Self gave a completely different oral confession, this time saying he’d struck the girls with a Coca-Cola bottle before leaving them in a bayou. Despite these contradictions, investigators pressed forward with their case.

Michael Self went to trial in 1973, and prosecutors built their argument largely around his confessions. Physical evidence was minimal and due to the state of the remains, the exact cause of death was impossible to prove. Still, jurors accepted that the girls’ deaths were homicides and found Self guilty of Sharon Shaw’s murder. He was sentenced to life in prison but was never convicted of Rhonda Johnson’s murder.

Self’s legal team appealed, arguing that his confession was forced. The courts didn’t agree and kept his conviction in place. For many years, it seemed the case was closed even as questions lingered.

Corruption Comes to Light

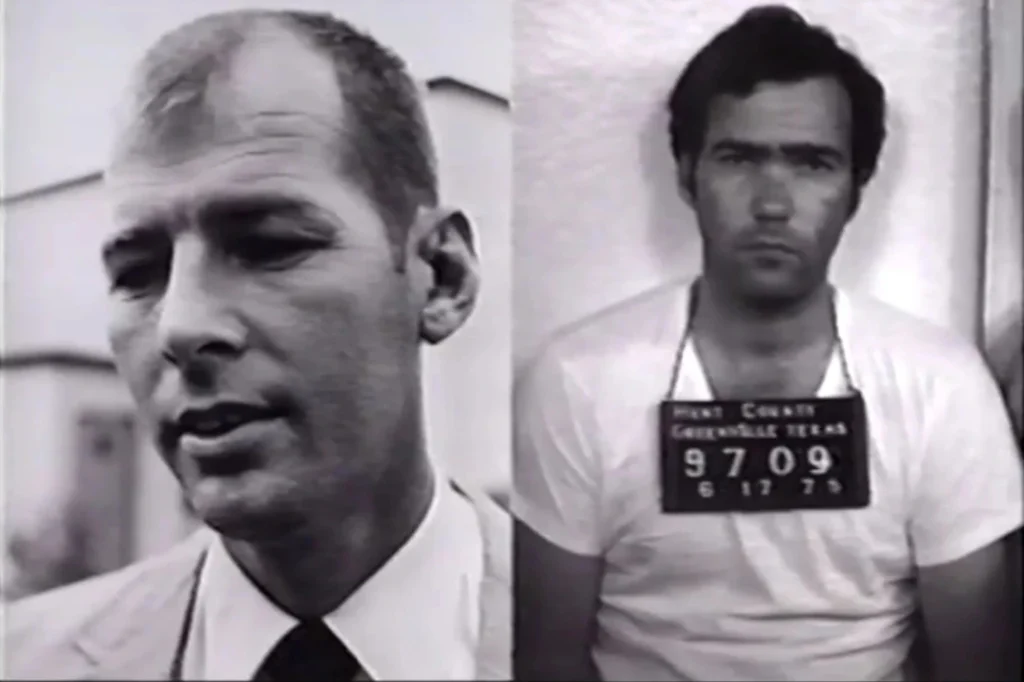

The story took another turn in 1976, when the very officers involved in Self’s case were arrested and convicted of multiple bank robberies. Police Chief Donald Morris and Deputy Tommy Deal, two of the men central to Self’s interrogation, were exposed as corrupt, criminal figures. This revelation caused many to question the integrity of Self’s conviction.

Self never stopped proclaiming his innocence. He filed petitions and fought for a new trial but judges refused to overturn his conviction. In a 1992 filing, his attorneys argued the confession was “not a voluntary act but a product of fear and intimidation.”

A former investigator later said, “The pressure put on Self was overwhelming. It’s troubling when the system’s protectors cross lines that jeopardize justice.”

Self would spend the rest of his life in prison. He died of cancer in 2000, still claiming he had been framed, per Wikipedia.

A Confession From Another Killer

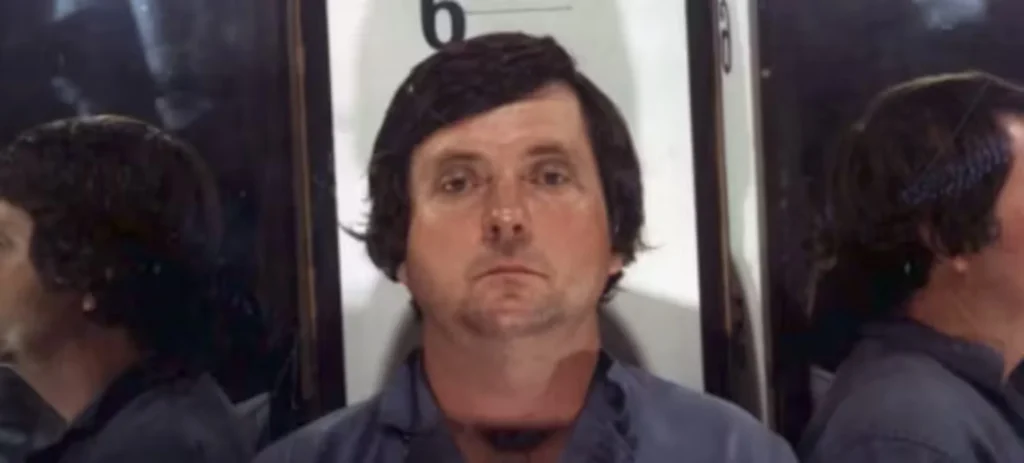

Two years before Self’s death, a man already serving time for murder shocked investigators with a confession. Edward Harold Bell claimed he had killed eleven girls in the 1970s, including Rhonda Johnson and Sharon Shaw. He referred to his victims as “the eleven who went to Heaven.”

Bell gave detailed descriptions of the crimes but prosecutors never charged him with the Johnson-Shaw murders. Some argued his statements lacked solid evidence while others believed he was confessing to crimes he actually committed. Bell remained behind bars for another killing until his death in 2019.

An official who reviewed the case years later said, “Confessions alone are not the gospel truth, especially when other confessions come to light, and the forensic evidence is limited.”

The murders of Rhonda Johnson and Sharon Shaw remain unsolved in the minds of many, despite Self’s conviction.

The case is also often linked to the infamous Texas Killing Fields, a desolate stretch of land along Interstate 45 that has been connected to dozens of murders and disappearances of women and girls since the 1970s. The area has inspired countless documentaries and even a 2011 movie, Texas Killing Fields, which loosely draws from cases like this one.